Posted on 24 April, 2020 in category: Interviews, Reflections | Tags: Autism, Interview, Science, Steve Silberman

Author: George Karouzakis

The 20th century, apart from being a period of great scientific achievements and discoveries also had several dark sides. We all know what happened during the two World Wars, with the use of the atomic bomb, the Holocaust, and much more. The drive for progress has often been accompanied by atrocities and misconceptions that have made difficult or destroyed the lives of thousands of people.

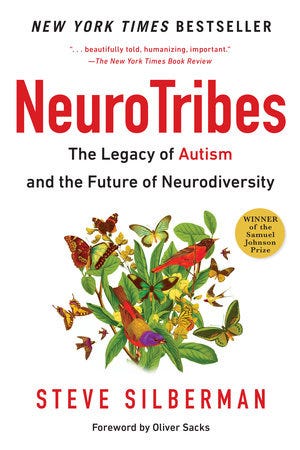

Similar misunderstandings still persist today, and are explored in an exemplary way in Steve Silberman’s book “NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity”. Silberman is an award-winning science reporter in America. After years of searching and studying, he has produced a book that retraces the history of autism with sobriety and clarity, putting the subject into a whole new perspective. It’s no wonder that “NeuroTribes” has been translated into 16 different languages and been awarded major honors, such as the Samuel Johnson prize for non-fiction, the California Book Award, and many others.

The early chapters of NeuroTribes focus on the discovery of this condition in the 1940s by two scientists who lived in different parts of the world: pediatrician Hans Asperger in Austria, and the psychologist and child psychiatrist Leo Kanner in America. For a long time, the two nearly simultaneous discoveries were considered a coincidence, but Silberman has uncovered previously hidden connections between the two researchers. Asperger and his colleagues in Vienna were the first to observe the distinctive constellation of behaviour that defines autism in their young patients. In the increasingly dark shadow of the Nazis’ eugenics laws, he spoke for the special abilities, intelligence and gifts possessed by autistic children and adults, saying they had a valuable place in society. Kanner held a different view: that the intensely focused interests of autistic people was a sign of pathology and bad parenting. Unfortunately, Kanner’s view prevailed for several decades.

Starting with the different approaches of the two scientists, Silberman critically analyzes the social and scientific research trends that have been associated with autism, highlighting the negative consequences of clinical stereotypes of autistic people.

In the first decades of the 20th century, experts interpreted the social ineptitude of autistic children, their early abilities, and their passion for rules as a form of childhood schizophrenia or the result of parental misconduct. Disastrously, Kanner and his colleagues blamed cold, unloving “refrigerator mothers” for causing autism in their children, making the condition a source of stigma and shame for families.

Silberman’s research excavates the truth behind the stereotypes and erroneous theories, bringing to light the new ways in we must approach the neurological diversity of humankind. The author does not idealize the capabilities of autistic children, nor does he overlook the problems they face or the hard work parents must do to help them.

With dozens of historical examples and interviews, Silberman shows that changing societal attitudes to autism — which has long been regarded merely as a set of defects and malfunctions — will both enable families to reach a state of acceptance, and help science to improve the lives of people affected by it.

Steve Silberman answered our questions in a follow-up to the Greek edition of his book by the publishing house Potamos.

– The adventure of autism, as it appears in your book, relates to some of the most serious events of the twentieth century — from the rise of Nazism, to the emergence of anti-science movements. What do you think are the most notable events that have shaped our beliefs on autism?

The biggest influence on society’s perceptions of autism was the work of child psychiatrist Leo Kanner, who claimed to have discovered autism in a 1943 paper that made him the world’s leading authority on the subject. In some ways, Kanner’s work was very insightful, but in other ways, it caused great harm to autistic people and their families.

Kanner memorably described the constellation of behaviors in his young patients in such a way that other clinicians could recognize it, which was good. But he also described the children he was taking care of as being disinterested in people — even their own parents — and living in their own worlds. In truth, autistic people do form meaningful attachments to the people in their lives, they just do it in their own ways. At various points in his career, Kanner blamed autism on emotionally cold and uncaring parents, which did tremendous damage to autistic people and their families for decades to follow, as psychiatrists recommended placing children in mental institutions “for their own good”. This was terrible.

Kanner also insisted that autism is very rare, while it is not. In fact, it’s one of the most common disabilities. This mistaken belief also became the foundation of the anti-vaccine movement later, when clinicians broadened the criteria for diagnosis to reflect autism’s true prevalence, but the lay public was not informed and became alarmed at an apparent rise in the number of cases. This was seriously damaging, and we are still suffering the consequences. There were more notable events in the history of autism, described in depth in my book.

Previously, scientists were widely trusted as arbiters of objective facts; now, the notion of objective facts has been cast into doubt. Some of this is highly intentional.

– So, what are the strongest stereotypes that have prevented a deeper understanding of autism, both in the scientific community and in society in general?

The three most damaging stereotypes that have influenced society’s perception of autism were that autism is strictly a condition of childhood when it’s a disability that requires support throughout the patient’s lifespan; that autistic person lack empathy and other human feelings when they feel things very strongly — they just can’t always put their feelings into words; and that autism is rare when it’s actually common.

– Do you think that Asperger’s primary findings on the patient’s abilities, and not just their difficulties, were stifled and silenced in the Nazi eugenics climate of his day?

The fact that Asperger was working in a clinic that was taken over by Nazis in the late 1930s surely had a profound effect on the reception of his work, making it virtually unknown for most of the 20th century outside of a small circle of specialists. It’s likely that Asperger emphasized the potential of some autistic people to make contributions to society — as indeed they can! — to save at least some of his young patients from death.

– At the same time, in the US, psychiatrist Leo Kanner disoriented the scientific community, shifting their focus from the right approach to the problem. Do you think that the way in which people and scientists treated autism during those years was related to their false beliefs regarding many other social and medical issues?

Yes, I do. In many ways, the story of autism in the 20th century was a story of two competing models — Kanner’s and Asperger’s. Kanner’s model prevailed unchallenged for decades; then in the 1980s, British cognitive psychiatrists Lorna Wing and Judith Gould quietly resurrected Asperger’s views, because in many ways they were more accurate. However, until my book came out, hardly anyone knew that had even happened. The errors that Kanner made had a devastating impact on autistic people and their families for a very long time.

– How do you explain that today, in the 21st century, despite the spectacular evolution of the scientific world, there are large parts of the population who are still challenging Science and its progress, refusing, for example, to vaccinate their children?

One unforeseen and terrible consequence of the spread of social media is that people are able to seal themselves off in “bubbles” of information that reflect their own biases. Previously, scientists were widely trusted as arbiters of objective facts; now, the notion of objective facts has been cast into doubt. Some of this is highly intentional. For example, oil companies have spent millions of dollars for decades, casting doubt on the motives of climate scientists, to protect their own business interests. The current President of the United States, Donald Trump, constantly lies to cover up the fact that his campaign received Russian assistance. Many of those who claim that vaccines or toxins cause autism to sell phony health supplements to parents. In each case, sinister motives lie behind the denial of truth and facts.

– Do you find that over-networking in our contemporary world also dispels our prejudices more easily? Is there a way to face this problem?

I was one of the people who hoped that network technology would conquer prejudice by enabling people all over the world to share their experiences. Unfortunately, the opposite has happened. Instead of bringing people closer, social media have caused society to fragment even further, into warring tribes.

– Your book talks a lot about neurodiversity, as you recognize the positive dimension of certain problems such as autism. But dominant notions like “good vs evil”, “healthy vs ill”, “normal vs abnormal” are still based on old archetypal models. Does it take time to change some of these kinds of viewpoints?

Yes, social change on important issues takes a long time, but I’m still hopeful about the progress that will come. When I was a teenager 50 years ago, homosexuality was still classified as a mental illness or even a sickness. Now, I’m a happily married gay man. That’s a lot of progress in one lifetime. It’s important to maintain hope while doing the work necessary to produce positive social change.

– You refer to the positive way in which Barry Levinson’s movie “Rain Man” has influenced public opinion on autism. Do you think that pop culture generally is a medium that can even help or affect scientific evolution in a progressive way?

One of the reasons why it’s so important to see accurate portrayals of autistic people in media is that it humanizes the condition, and provides role models for young autistic people. The same is true for people of different races, nationalities, sexual orientations, and gender identities. As media portrayals of various kinds of human beings become more accurate, researchers will better understand the nature and consequences of their own work, which will make better science.

© Copyright 2001-2020 Thales + Friends.

designed & developed by ELEGRAD